Neurodivergent reflections on the role of silence in Music Therapy

Content note: domestic violence, firearms, death

June 21, 2019

written Jessica Leza, MA, MT-BC

Commercial use, reproduction/copying of content, scraping content, or using this essay for machine learning or AI training is strictly prohibited.

____________________

I’ve never been a big fan of silence.

To be perfectly frank, I don’t even believe in silence.

(It’s a purely theoretical construct, not something I will ever experience. My neurodivergent brain, equipped with hypersensitive hearing, is too finely tuned to ever allow me this experience.)

Even in the quietest moments, when I am inside,

in my house,

Alone,

The fan hums

(On the other side of the house).

The refrigerator buzzes.

(Everything buzzes!)

The computer fan whirs and spins, whirs, and spins,

picking up speed and slowing down again to create its own erratic electric rhythm.

Outside, a blue jay screams an alarm.

A neighborhood dog barks a block away. Car doors slam. There is the quiet roar of the traffic traveling on the freeway a few miles away.

I hear a passenger plane flying far overhead

(or a helicopter. or some military aircraft I cannot label.)

(My husband doesn’t seem to understand why I am so attentive and excited when the flight paths to the airport 40 miles away have changed and the planes start coming by once every few minutes and I can hear each one approaching and then leaving in a steady roar that lasts nearly an hour like some kind of auditory passenger plane parade.)

I hear a gun being fired two miles away.

(Yes, when you fire your gun to intimidate some woman I can hear your rage miles away.)

I hear a baby bird’s tiny high-pitched chirps.

(I picture it fluttering its wings, begging its mother for a bit of seed).

The worst is when I can hear my neighbors,

Across the street,

Down the corner,

Fighting,

Screaming,

Each word,

Each time she hits the wall,

Each time she slaps her hands together,

Each time she shouts at him, “go ahead, try it!”

And I can tell from across the street,

Inside my own house,

That she has experienced more frightening things

Than whatever is happening to her

Right now.

So no, I don’t really believe in silence.

In the most literal sense, silence is actually made out of a rich tapestry of sounds that chaotically wash together in waves of information about the living, moving world around us. Even in the most sound-proofed environment humans have created – the anechoic chamber – you can still hear two sounds: the low tones of the blood rushing through your body, and the high-pitched whine of your nervous system. I don’t need an anechoic chamber, I can hear my blood rushing through my body just fine and it’s already unnerving enough, thank you very much.

… Sometimes when I hear a subtle but omnipresent high pitched buzzing whine, I wonder – is what I hear the electronics outside of me, or the electronics inside of me? …

Neurodivergent perceptions aside; silence is something I have come to value greatly within the practice of music therapy.

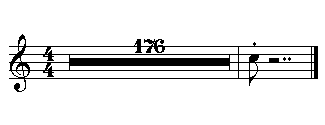

As musicians, music therapists know the value of silence. We know how to shape a silence by attending to what happens immediately before and after. We know that the moments of silence within a piece are what give music its rhythm, and we know a careful and honest use of silence can flavor even the most familiar music with our own unique personality.I always think one of the most visceral parts of a performance is the moment a piece ends and the audience is silent. As a performer, I love to see how long I can drag out that silence and live in that awkward moment when it seems like time is standing still and rushing forward and stretching out into a vast gulf, all simultaneously. Being able to sit in that moment before the audience responds is so uncomfortably, profoundly aesthetic.

In these cases, the silence becomes an act of waiting.

(Wait for it,…. Wait for it,….

Now? Is it now? Is this it? Is this art?)

And the waiting becomes an act of patience. This act of patience – bearing with the discomfort of the uncertainty of prolonged silence – becomes a preverbal act of compassion that connects us to our shared humanities.

(Especially when you’re trying to be patient within a society that times our interactions with one another to the minute in order to determine who owes who and how much. Time is money, people! Patience is expensive! Silence is a luxury good! How much will you pay me for writing this?!)

As music therapists, we can use aesthetic experience as the rationale for suspending these mundane expectations and experiences of silence as a time-waster or profit-stealer or lazy-maker, and we get to apply the magical tension and discomfort and euphoria of silence, to open the door to healing and positive change.

Melanie Yergeau says, “my silence isn’t your silence. My silence is rich and meaningful. My silence is reflection, meditation, and processing. My silence is trust and comfort. My silence is a sensory carnival. My silence is brimming with the things and people around me — and only in that silence can I really know them, appreciate them, “speak” to them, and learn from them.”

I’ll never forget when during my internship in a medical setting I had a client who was slowly dying and no longer participating in her own care. She just sat and sat and sat, looking blankly ahead at the soap dispenser on the wall.

I tried to talk to her, and she was hopeless and helpless in the face of her unresolved issues. When I played guitar and sang familiar tunes for her, she just wept quietly.

Trying to verbally intervene in her grief, I had lightly affirmed, “it’s not your fault, this terrible thing that happened to this person you loved, it’s not your fault.” I knew without her responding that she didn’t believe me, but I didn’t know what else to do.

So I put my hand on top of hers and looked out the window,

(Eye contact is not the only way to make contact),

and we sat in silence,

(I say we sat in silence, although it’s not true, because the noise of the hospital continued on as it always did).

We sat, looking out at the Phoenix desert together, saying nothing, doing nothing, the time stretching on into the afternoon.

I only spoke to her again to excuse myself when it was time for her to receive a medical treatment.

When I visited her the next day, she greeted me by saying, “you were right.”

I was so confused. I was right? About what? We had barely spoken the day before.

She explained.

While we sat, unspeaking, she had experienced an enormous breakthrough. She felt able to release a great burden of guilt and shame that had been plaguing her, and now she was ready to sit with me and make some plans for the things she wanted to do before she died. She wanted to make something, something purple for the loved one she was ready to grieve for in a new way.

I was shocked.

Until then, I had never fully realized what it means when Fritz Perls and others say, “it’s the relationship that heals,” much less had I realized that this therapeutic relationship could be forged through an active and authentic act of patience in the form of sitting in silence.

In therapy, in music, and thus in music therapy,

waiting, being silent, being patient, just waiting, prolonging expectation, just waiting patiently and taking the time to enjoy the discomfort of waiting, is one of our most powerful tools – no matter what ‘population’ we’re working with, and even when that silence is actually expressing the full cacophony and chaos of a living environment.

As Julia Miele Rodas writes in Autistic disturbances: Theorizing autism poetics from the DSM to Robinson Crusoe, “In fact, while it may be socially or intellectually difficult to encounter, silence may certainly be a deliberate choice, expressive and creative. … Silence is not necessarily inert or passive, but may be expressive, central, significant” (pp. 132, 184).

Read more / Works Cited

Georgiou, J., & Reynolds, J. (2018). The use of silence and silencing in group counseling: Productive, unproductive, and misunderstood. The Practitioner Scholar: Journal of Counseling and Professional Psychology, 7, 112-128. Retrieved from: https://www.thepractitionerscholar.com/article/view/18186?fbclid=IwAR1-t0HWlgUYbLzJfCYK3oLYuvhs-fElsKoMtz1tLqsekgZaAHIfoLrmBgY

Rodas, J. M. (2018). Autistic disturbances: Theorizing autism poetics from the DSM to Robinson Crusoe. University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Yergeau, M. (2012). Socializing through silence. In Loud Hands: Autistic people, speaking (pp. 223-224). Retrieved from: http://autistext.com/2011/10/24/socializing-through-silence/